Crunchapalooza!

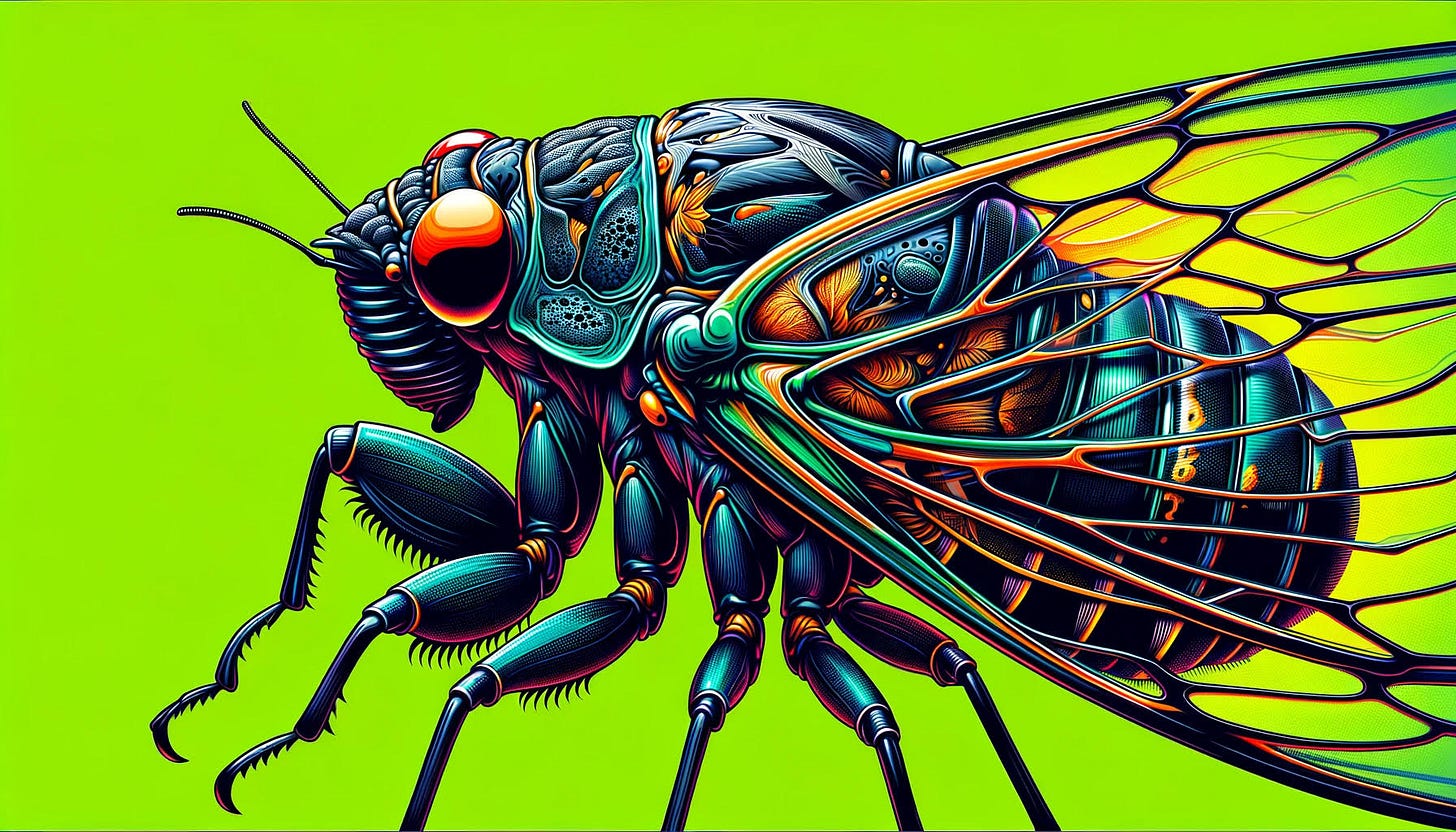

The cicadas are back! Red-eyed, super-loud —and now the future of food?

CHICAGO — Hellscape or heaven? It depends on your taste.

Summer has begun, and here in Illinois and in 16 other Midwest and Southern states, trillions of horny, red-eyed cicadas —two big broods of them—are bursting out of their 13-year and 17-year slumbers, blasting mating calls as loud as rock concerts.

Head over to the tall oak and silver maple trees lining the otherwise quiet residential streets of west suburban Chicago, and you will see these critters emerging from their underground tunnels—and in double, blue state and red state broods not seen emerging together since 1803, when Thomas Jefferson was President. Singing at levels of 90 or more decibels, these cicada choruses can get as loud as motorcyles revving up at full throttle.

These bugs are also wildly plentiful. Step onto a tree-shaded lawn in the leafy suburban enclave of Western Springs, and you will likely crunch down onto a mass of hundreds of cicada nymphs shedding their crispy exoskeletons before climbing their way up a tree trunk to mate in the branches above. Capture their ascent on Instagram, as did suburban Hinsdale resident Ken Sentano, and you might wish you wore a hat to avoid getting “drizzled” by what locals here call cicada rain— the tree sap these bugs consume and expel daily.

Creeped out? The “yuk” factor can be overwhelming for some—no question. As a kid growing up here, my brother would try to scare me with them, and succeeded.

But these days? Cicadas are also emerging as the latest stars on today’s sustainable food circuit. Innovative chefs at high-profile restaurants and GenX influencers on TikTok—citing cicadas’ nutty flavor and crunchy texture—are harvesting them and creating dishes like cicada tempura and cicada-stuffed ravioli. Social media is abuzz with home cooks sharing recipes and experiences, turning the once-dreaded emergence into a culinary celebration.

And here in Chicago, a new generation of climate-conscious chefs say they consider these meaty insects the future of food, along with the restaurants daring to serve them.

From Pests to Plates

“Are you ready for some Cicada stir-fried noodles, my friend?” Chef Joseph Yoon asked during the first day of Chicago’s Cicada Week food fair, the city’s first such “alt-meat” event in Chicago’s otherwise internationally famous history as being the center of America’s beef and pork meatpacking industry after the Civil War through the 1970s.

Yoon and some of Chicago’s chefs specializing in today’s six-legged cuisine are serving up cicada tacos, cicada sushi, deep-dish cicada pizzas and other insect-inspired concoctions. A local suburban brewery in Lombard has joined the party, offering beer and whiskey shots a la cicada.

Yoon, the founder of Brooklyn Bugs, a small restaurant he opened in 2017 and has since re-configured to focus on teaching new chefs and everyday consumers how to add insects to their menus, is leading what he calls “the nation’s first edible insects movement.” Yoon keeps jars filled with cicadas and other insects to add to what he’s cooking up in his YouTube videos. [A recent interview video he made for WBBM Radio-Chicago and posted on TikTok went viral.]

“Cicadas have a nutty taste and a vegetable quality to them,” Yoon says. “Black ants taste zesty and citrusy. Super worms taste cheesy. We have so many different flavor profiles.” Some chefs grind the bugs up and mix the powder into bread or use it to garnish the rim of a drink glass, like salt on a margarita. “When you think about the fact that there are more than 2,000 varieties of edible insects in the world today,” Yoon says, “we’re looking at a cornucopia of culinary potential.”

Climate Change Catalyzed

But for all the fun and fanfare, this new culinary frontier is simmering into more than just another trend. Climate change is the driving force behind much of today’s growing interest in promoting the consumption of edible insects.

By 2050, scientists and food industry innovators predict, extreme weather events, water scarcity and declining soil health will be threatening food security, and not just in today’s global hot spots. Insects, with their minimal environmental footprint, can present a viable solution for us all. It’s estimated that the world’s population will reach 8.5 billion in 2030, and could increase further to 9.7 billion by 2050. “At the rate that we’re going now,” Yoon says, “we’ll run out of resources to feed the growing population.”

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), a Toledo, Ohio-based nonprofit advocating food system innovation, about 2 billion people worldwide—roughly a quarter of the population—already add insects to their diets. In countries including China, Thailand, Mexico, and Ghana, bugs are a traditional food source, and a gluten-free, protein-rich delicacy offering a healthy supply of nutritious vitamins and minerals.

Insects are also environmentally friendly, says May Berenbaum, an entomologist at the University of Illinois. They require significantly less land, water, and feed than traditional livestock, and their cultivation produces fewer greenhouse gases. According to a report by Barclays, the insect-based food market in the United States and Europe—much slower to embrace insects as food—is now expected to reach $8 billion by 2030 as younger consumers and food industry innovators seek more sustainable and eco-friendly alternatives.

Signs and Signals

All that said, however, the integration of insects into Western diets is not without its challenges. “There’s no question that the concept of eating bugs represents a big shift in how we think about food,” says Berenbaum.

But as cicadas emerge this season, she says, they‘re also being viewed by some as being more than just a natural phenomenon. “They are catalyzing us into thinking more creatively about what climate change might start to require of us and how we can become more resilient to it in the years ahead.”

Adds long-time Hinsdale resident Ken Sentano: “We don’t frown at caviar, nor frogs, nor cow’s liver here in the Midwest. Add a few cicadas into our diets now, and our kids won’t think twice the next time these 13- and 17-year cicada broods show up by the trillions.”

Point served.

What is your take on this new food frontier? With climate change already upon us, do you think insects might be in your culinary future? Got a recipe to share?