Memes are having a moment.

As the 2024 presidential campaigns get under way, many Americans have simply tuned out. But not on social media.

Memes—those memorable, unscripted mishaps, behind-the-scenes comments or funny asides caught on 30-second video or audio clips that get shared by millions on TikTok or Instagram? They are as popular as ever.

And when they go viral, they stick. Remember when a fly landed on then-Vice President Mike Pence’s head during a 2020 debate with Kamala Harris? Or last summer, when President Joe Biden took a nosedive after delivering remarks at an Air Force Academy graduation ceremony? Donald Trump is another famously memed figure in American life. Photographs of him falling asleep during his trial last month in New York, and subsequent fraud conviction, also have gotten shared by millions. And let’s not forget the recent TikTok photos and shares about the upside down flag—a “Stop the Steal” symbol— displayed by Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito and his wife outside their home.

Long dismissed as inside jokes with no political importance, memes are evolving into powerful political tools of persuasion this election year. They’re now being used to influence public opinion up and down the ticket, and more aggressively this year than the last time Donald Trump ran against Joe Biden for the White House.

“The 2024 election seems more destined to be waged in a media environment where a lot of sway voters will be forming at least some of their opinions based on funny videos that their cousin’s husband’s sister shares in the group chat,” says Clare Malone, a staff writer at The New Yorker.

No debate there. Memes matter. They can catalyze votes, change minds and are being used by politicians to organize supporters—directly—to serve as “brand ambassadors” and influencers of public opinion.

Fun versus Fights

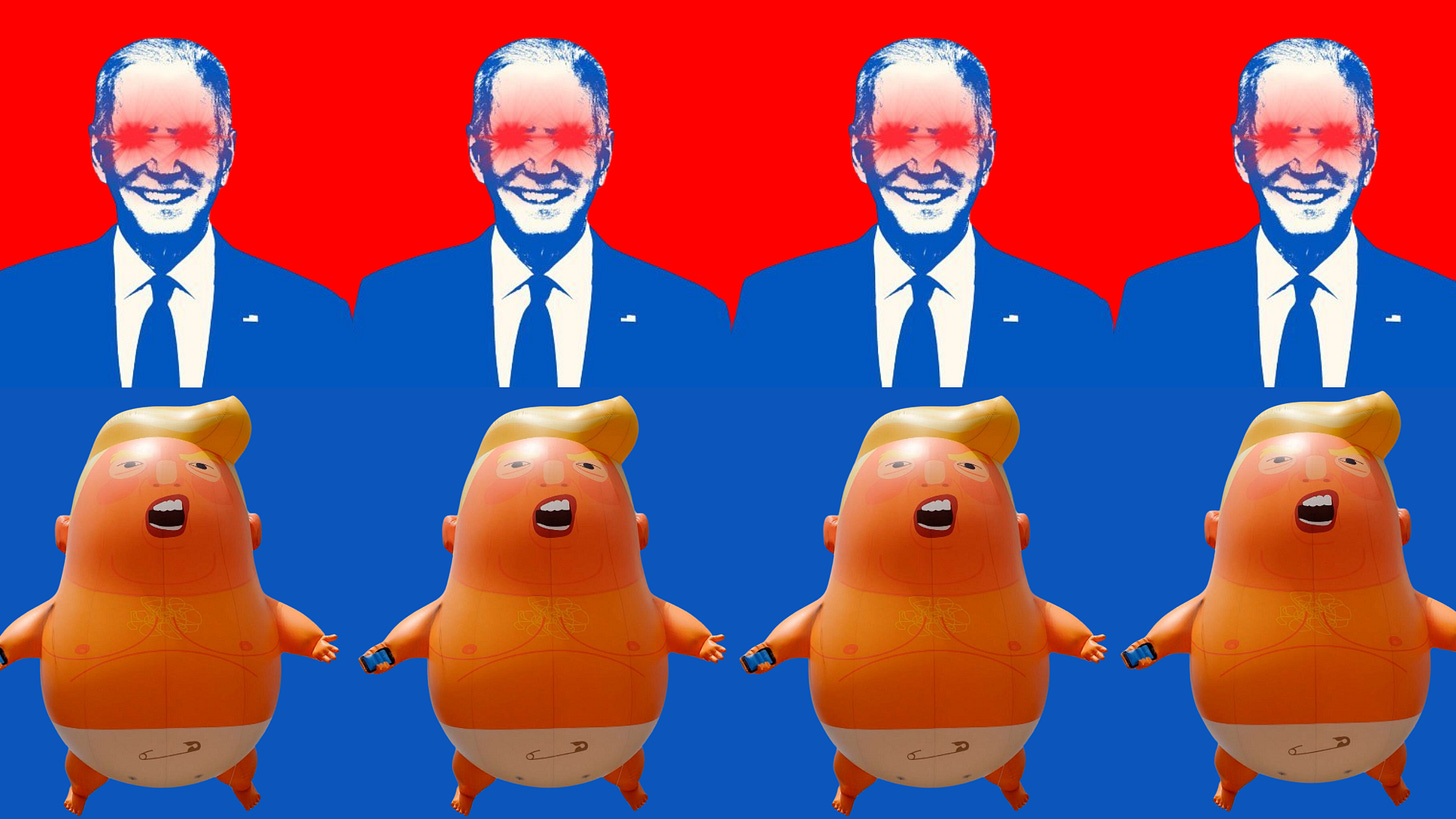

If you use a social media platform—and we know most of you do—it’s more than likely you’ve seen a satirical meme (or created one as a form of political satire) which made you and others chuckle. [Think ‘Trump Baby’ —an angry orange baby holding a mobile phone—from the last presidential election, and check out ‘Dark Brandon’ from this election season.]

They’re like editorial cartoons— but with one huge difference. These digital memes can be made by anyone who knows how to use Photoshop, and, depending on their appeal, can be distributed to millions in a heartbeat, immediately off the news.

Politicians, themselves, now make them. One meme about aging that is still making the rounds since January is a photo of a birthday cake given to Joe Biden, engulfed in flames (too many candles), which Biden’s communications people created on his birthday to disempower detractors from creating their own. “He knows he’s not getting younger and so the way to deal with concerns about his age is to make jokes about it,” said Malone.

Donald Trump also went onto the PR offensive, making a “rebel”meme out of his mugshot showing a facial expression he rehearsed and then tweeted out himself, immediately after his August 2023 indictment on racketeering and related charges. According to Trump aides, the mugshot meme was used by Trump to signal to his supporters that his indictment “would be handled as being a part of his ‘outlaw brand’” rather than as anything else.

But what happens when memes go beyond a laugh or an obvious PR spin campaign? When a meme is no longer shared simply as an inside joke? Or when bad actors disguise political disinformation or hate speech as a meme, to enable wide and semi-covert distribution outside the moderated media ecosystem?

One controversial example still being used by some internet subcultures is Pepe the Frog. What began as a harmless cartoon has morphed into an image used by the alt right to spread hate by white nationalists.

As this year’s election season heats up, PBS Learning Media, a resource for high school teachers, is distributing a new video to teach students about the messaging power of memes. In a new video on meme-watching, students are taught that there are “good memes” and there also are bad ones that are short bits of social messaging advocating harmful ideologies “disguised” with humor. The video also points out memes used by election-year candidates to score political blows, sometimes below the belt—with a smile.

Danger Zones

While many memes are particularly popular among GenZers, they are not limited to a specific age group. But their excessive misuse can lend itself to more harmful ideas getting disguised as humor, and lead to what some call “mematic warfare.”

Just this past week, at the McCain Institute’s 2024 Sedona Forum in Arizona, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said social media sites like China-owned TikTok are partly to blame for algorithmically promoting memes and other “content without context” to share criticism of Israel’s war effort against Hamas in Gaza while diminishing the prominence and reach of opposing opinions also expressed on the site. Blinken also cited, in part, a changing media environment in which many people “no longer all read from the same authoritative news sources and instead learn about current events on chaotic social media feeds.”

According to Joan Donovan, the director of Harvard’s Technology and Social Change Project, which published research on Covid misinformation and the Jan. 6 Capitol riot, social media are becoming on-ramps for small and extreme subcultures to amplify their political views, manipulate the media and provide “first takes” of disinformation campaigns to fight opponents and identify “political enemies.” Donovan’s research reveals how information “disguised as somewhat humorous and harmless memes” was used to organize the Proud Boys and other internet subcultures to participate in the Jan. 6th attack on the U.S. Capitol.

Donovan, a co-author of the 2023 book, Meme Wars: The Untold Story of the Online Battles Upending Democracy in America, says efforts to regulate social media are not attempts to dismiss free speech, but rather efforts to “better balance” how the internet and algorithms interact with our culture, and then interact with our politics.

“There are now systems in place to take speech that has an agenda or is harmful and to amplify it, so that it becomes so omnipresent that it cannot be avoided and therefore, be used to change people’s minds,” Donovan said in an interview. “ …What many people see now on social media— when they’re just there to maybe just RSVP to a niece’s wedding—are meme after meme or news article after news article highlighting a specific point of view, which can suck us down a rabbit hole, regardless of whether we wanted to be there or not. …The trouble is that tech companies are still not creating guardrails to reign some of this in. .. and we need to start considering how to do this to support the integrity of our information systems and our election systems.”

“…Memes are now giving extreme beliefs and disinformation a better chance to not only be seen and heard loudly but also to take those people who can be persuaded quickly from the wires to the weeds and inspire offline action,” Donovan added.

What now?

So how might we reasonably expect memes to keep evolving—and how might we go about creating ways now to moderate their use and veracity in this, or any other, high-stakes election year?

Meme Wars co-author Emily Dreyfuss agrees that today, government regulation of tech companies, requiring them to moderate the content on their sites more rigorously, is critically needed to create the guardrails companies will need “to build trust and make our democracy more measured and effective.”

Otherwise, Dreyfuss adds, “aggressive campaign rhetoric and hate speech will continue to be turned into memes and into fodder for ‘jokes’ and persuasion strategies, which then can be used to push an extreme agenda forward with a level of influence not possible before the internet.” Donovan likens the use of political memes now to “a chess match being waged by political subcultures and small-member extremes” to win influence.

The New Yorker’s Malone, in a recent conversation on the New Yorker Radio Hour, says her theory of American politics, especially after observing the political campaigns conducted during the past decade, “is basically that very little of them (campaigns) are really about policy anymore. It’s now all political pheromones. …If a person (running for office) parries back with a humor meme that you like, and it seems to be done well and it’s not corny, then yes, maybe political memes will work” to help influence someone’s vote, she says—and at least for a variety of influential groups.

New rule? Memes aren’t just funny inside jokes anymore that can foster a sense of exclusive community.

Memes can now deliver a laugh as easily as a vote for the other side.

This story was updated to reflect new developments.

What’s your take on memes? Got a favorite, or one you think has spread disinformation? Share it here. We’ll be curating some of them for an update on their influence later this election year.